Developing a Biosecurity Culture in the Middle East

The COVID-19 Pandemic Underscored the Need to Safeguard Potentially Hazardous Viruses and Bacteria

NISREEN AL-HMOUD, PROJECT DIRECTOR, CENTER FOR EXCELLENCE IN BIOSAFETY, BIOSECURITY AND BIOTECHNOLOGY, ROYAL SCIENTIFIC SOCIETY, JORDAN

Ensuring that nonstate actors can’t acquire and weaponize viruses, bacteria and other biological material to threaten international peace and security has been the goal of U.N. Security Council Resolution 1540 of 2004 and the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC) of 1972.

Signatories of those two agreements include almost all of the countries of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) — including Jordan — yet progress has been uneven toward stiffening regulations to avoid disaster should hazardous biological materials fall into the wrong hands.

To fulfill the requirements set forth in these international legal instruments, countries in the region, whatever their initial level of development, need to build experience, expertise and infrastructure. The objective of this article is to summarize biosecurity-related projects in the Middle East and their contribution to the ongoing construction of a global network committed to ensuring that biological materials and technology are used strictly for peaceful purposes.

The role of nongovernmental and other civil society organizations has long been neglected by governments in the quest for a world secure from the threat of biological weapons or bioterrorism. New trends illustrate a greater appreciation of the need for cooperative partnerships.

Because of the unique political and geostrategic circumstances of the region, civil institutions in the MENA region have extensive firsthand experience in dealing with arms control and nonproliferation issues.

For example, a task force convened between 2010 and 2012 to discuss implementing a zone free of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) in the MENA region. The task force was composed of policy and technical experts from the region, acting in their private capacity, in addition to facilitators and observers from Europe and the United States.

The group chose to focus initially on biological weapons. It is an area that — in comparison to other WMDs — offered the fewest political obstacles to constructive discussion.

Another effort was a bioengagement program conducted by the Center for Science, Technology, and Security Policy (CSTSP) in the broader Middle East and North Africa (including Afghanistan and Pakistan). The program focused on building trust and partnerships between scientists from the U.S. and the region to promote safe, ethical and secure life sciences research.

Bioengagement programs faced interconnected obstacles, including lack of money and sustainability. Demonstrating the success of bioengagement programs is inherently difficult because no evaluation criteria exist to measure the ultimate goal of the programs, which is to prevent terrorist acquisition of tools and expertise and identify possible uses quickly.

Coordination among funding agencies and donor countries is a separate challenge that affects the long-term sustainability of bioengagement programs in certain regions. A large number of funding agencies and implementers support or carry out bioengagement activities, particularly in regions where terrorist or biological weapons concerns are high.

In Afghanistan, the Middle East, North Africa and Pakistan, differences in scientific capacity further complicate the development of programs. For example, experience with securing biological contagions in laboratories varies greatly across the region.

On the other hand, the program outlined new opportunities for bioengagement and specific improvements to the process of bioengagement that accounted for national capacity differences. Recommendations were based on challenges, gaps and needs in addressing biological risks. Of importance, the opportunities and approaches would contribute to the decadeslong concept of a web of prevention, in which a variety of programs are carried out to address security concerns.

The EU Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear Weapons Center of Excellent (EU CBRN CoE) is a worldwide initiative jointly implemented with the European Commission’s Joint Research Center (EC-JRC) and the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI).

The initiative aims to mitigate CBRN risks of criminal, accidental or natural origin by promoting a coherent policy, improving coordination and preparedness at national and regional levels, and offering a comprehensive approach covering legal, scientific, enforcement and technical issues. The initiative mobilizes national, regional and international resources to develop a coherent CBRN policy at all levels to ensure an effective response.

So far, much of the European Commission’s CBRN training has been in the former Soviet Union, focusing on nuclear safeguards and security. However, growing demand for nuclear energy, biotechnology and chemical substances in parts of Africa, the Middle East, and South and Southeast Asia requires an expansion of such training. This shift reflects the requirement under U.N. Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1540 to assist any countries in need. The Group of Eight industrialized states has agreed to facilitate this assistance.

The CoE contributes to the achievement of the key requirements of the resolution by supplying assistance and technical support to help governments assess national and regional needs and to help develop tailored CBRN CoE projects to plug capability gaps.

The EU initiative in the Middle East undertook

12 projects starting in 2013. The projects dealt with key CBRN issues such as improving CBRN legal frameworks, enhancing chemical and biological waste management, assessing the risk of CBRN misuse, improving biosecurity and biosafety, building capacity to counter illicit trafficking in chemical agents or nuclear or radiological substances, raising awareness about CBRN-related topics, bolstering emergency response to CBRN events, and promoting secure exchange of data about CBRN events.

One of the latest projects launched in the Middle East is titled “Strengthening Capacities in CBRN Response and in Chemical and Medical Emergency.” The overall objective of this project is to develop a comprehensive intercountry (Iraq, Jordan and Lebanon) and interagency structure to coordinate, establish and implement CBRN incident response throughout the region.

It will address national needs in the countries by improving existing CBRN emergency response capacity and providing technology and training in prevention, preparedness and response.

The Biosafety and Biosecurity International Consortium

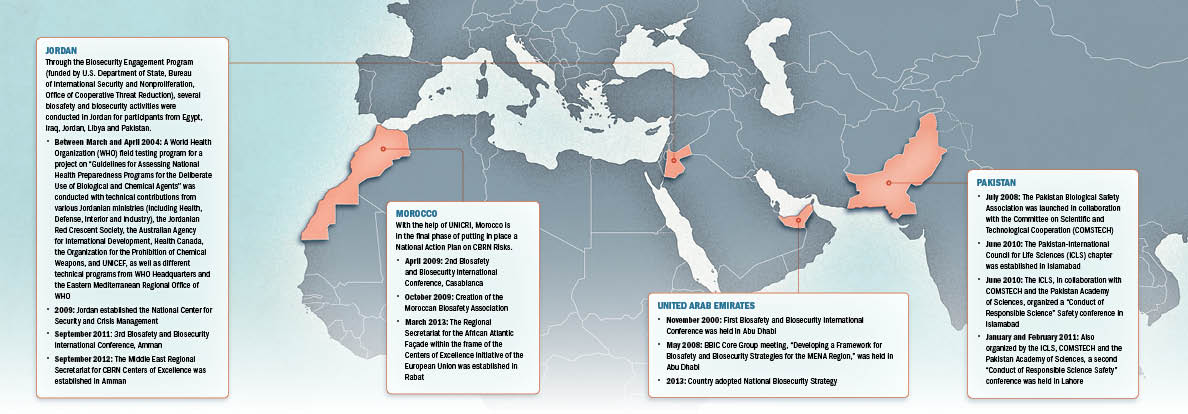

The Biosafety and Biosecurity International Consortium (BBIC) enables countries of the MENA region to identify biological risks to which they are exposed and mitigate them through national and regional biosafety and biosecurity strategies underpinned by legislation and human and physical infrastructure.

The approach is a whole-of-government, one-world view of biological risk across the spectrum of natural, accidental and intentional threats as they pertain to humans, animals, plants and the environment, including water. The network’s activities include holding biannual conferences, designing national strategies, and creating national and regional biosafety associations.

The BBIC helped establish two biosafety and biosecurity training centers for the region, one in Jordan and the other in Morocco. It also approved several biocontainment labs to undertake research and investigations in a secure setting. Pakistan and Morocco are among the countries to host these biocontainment labs.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Regional networks and activities are appropriate forums to help overcome UNSCR 1540 implementation challenges. Many experts from the MENA region are involved in these regional activities and initiatives. By bringing champions from each of the relevant sectors together, these initiatives build networks of experts both nationally and regionally to ensure that relationships are established to deal with a biological event before it happens.

By sharing experiences and knowledge acquired through such initiatives and networks, MENA experts can advise their national decision-makers. These networks also work across difficult political boundaries through sustainable connections. Such initiatives can play a valuable role in identifying mechanisms to advance the interests of all countries involved.

In a region with a number of politically sensitive boundaries, key elements that make any network function effectively are face-to-face meetings, workshops, seminars and training. Initiatives and related activities in MENA have promoted a better understanding of threat perceptions, built relationships among security experts, officials and academics, and served as a laboratory for new ideas.

However, to sustain the counter CBRN activities in the MENA region — such as training, policy development and capacity-building — a sustainable funding vehicle is needed to shore up implementation capacity of regional networks and ensure they can fulfill their potential as facilitators of security-related measures, including UNSCR 1540.

Particularly important is funding from private foundations to strengthen regional ownership and counter the perception that the process is driven by governments outside the region.

Sustainable and effective biosafety and biosecurity activities developed and implemented in the MENA region, with the assistance of thoughtfully applied funding and expertise, will strengthen regional and global security and solidarity.

Comments are closed.