Lt. Col. Ghassan Altassan, Saudi Senior Representative to U.S. Central Command

Lt. Col. Ghassan Altassan, Saudi Senior Representative to U.S. Central Command

Terrorist movements such as al-Qaida and Daesh managed to recruit tens of thousands of followers using emotionally laden narratives that speak to the fears, beliefs and prejudices of psychologically vulnerable people. Through such storytelling — which included more than 800 videos broadcast online — terrorists sought not just to shape attitudes of recruits, but to alter their behavior in the direction of violence.

Very little of this online content was specifically religious. According to the International Observatory for Terrorism Studies, religion accounted for only 2% of Daesh propaganda on the internet. Overwhelmingly, Daesh showed images of fighting, warfare and violence to sell the erroneous proposition that it was fighting against injustice and encouraging young men to join a “noble cause.”

By playing on viewers’ emotions, storytelling lured thousands of recruits to conflict zones to join a cause that bore no resemblance to the justice seeking it claimed to represent. The mass media inadvertently played into terrorist hands by rebroadcasting such Daesh internet content, most egregiously the video-recorded murder of Jordanian pilot 1st Lt. Muath al-Kasasbeh. Studies showed that viewers often didn’t distinguish between the original terrorist propaganda and its rebroadcast on television.

We in the counterterrorism community cannot neglect the power of storytelling in our efforts to defeat terrorist organizations. In refuting ugly, destructive terrorist propaganda, it’s important to touch viewers’ and listeners’ emotions through dramatic storytelling. Storytelling becomes the delivery method for anti-terrorism messages.

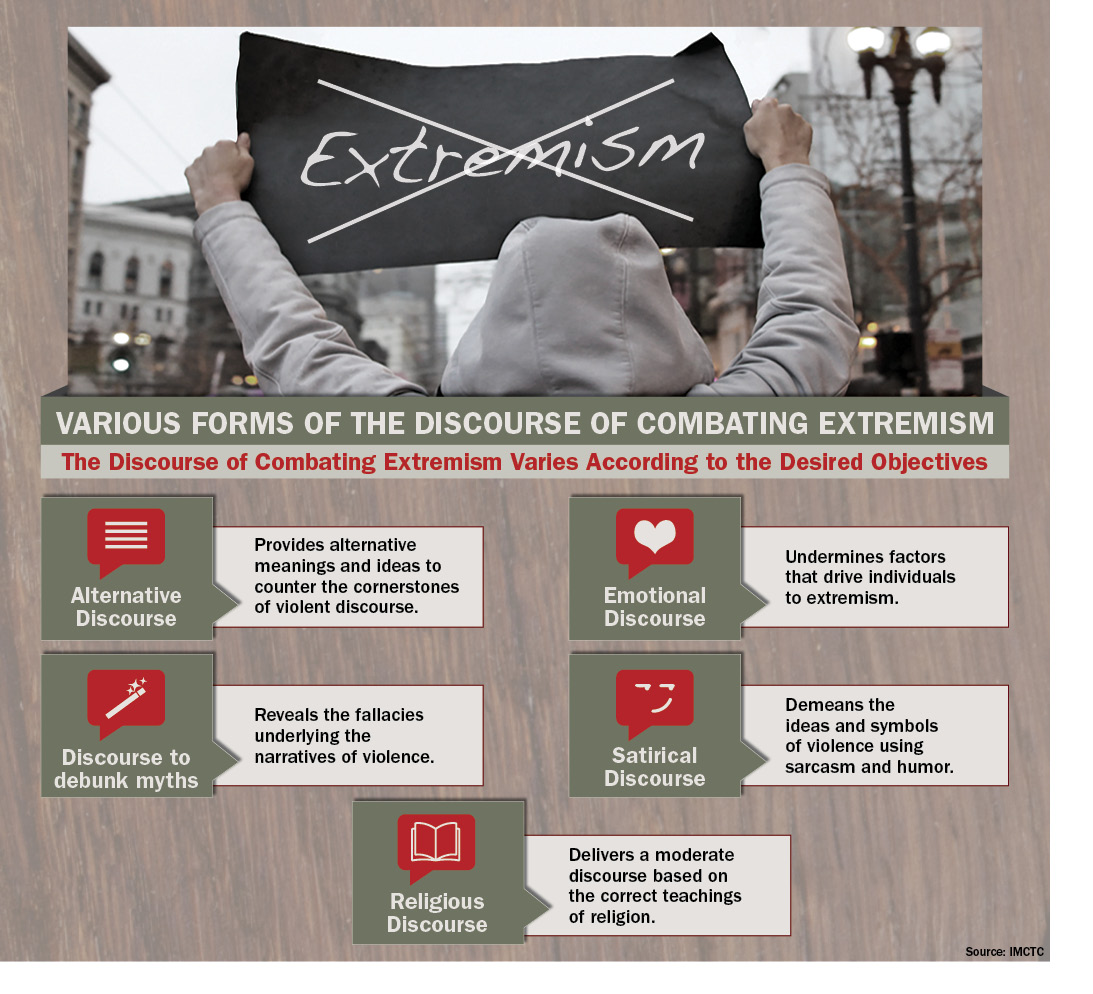

But we must do so in a way that reframes the enemy’s arguments. Our goal is not so much creating counternarratives to answer the lies of terrorists but creating alternative narratives that expose them for what they are.

Another name for these alternative narratives is dramatic soft power. News, analysis and discussion can succeed only so far in combating the ideology of violent extremists. We need to reach viewer sentiment through dramatic presentations of the evil of terrorism, whether it be through theater, television, cinema, literature or other arts.

Another name for these alternative narratives is dramatic soft power. News, analysis and discussion can succeed only so far in combating the ideology of violent extremists. We need to reach viewer sentiment through dramatic presentations of the evil of terrorism, whether it be through theater, television, cinema, literature or other arts.

Drama deals with human relationships in their complexity and can delegitimize terrorism at a gut level that changes attitudes among the audience. It builds awareness of contradictions in extremist ideologies not just at the level of reason, logic and intellect, but in the realm of emotion, subconsciousness and imagination. Exposed to hypnotic images produced by skilled directors, one’s body and senses grasp a reality faster than one’s mind can.

For example, four years ago Middle East Broadcasting Center (MBC) broadcast a 30-part dramatic series called Black Crows that portrayed the abuse by Daesh of war brides and sex slaves in Syria and Iraq. Millions of Arab-speaking viewers, many of them women, absorbed the reality of life under Daesh in its full horror.

Two years earlier, the same network broadcast episodes of Selfie about young men snared by the ideology of Daesh. In one memorable scene, a son fighting for Daesh holds a knife to the throat of his grieving father. This stark portrayal of family betrayal — a brainwashed son willing to slaughter his own father — outraged the audience.

Drama can also confront societal and global problems on which terrorist groups feed. Terrorists use emotions to present themselves as guardians of purity and justice who will remedy the unfairness of the world. This process of emotional stimulation works through propaganda tailored to the norms of the society it’s trying to manipulate. For those vulnerable to such manipulation, these emotional appeals build resentment and can lead to terrorist recruitment.

From the anti-terrorism perspective, drama offers a pathway to channel these sometimes raw emotions into positive directions. When a societal issue is presented dramatically in accordance with a person’s central beliefs, that person tends to accept the presentation as reality. In other words, storytelling that addresses problems nonviolently, yet still adheres to the values and beliefs of the audience, will be more persuasive.

We can see that storytelling in its many forms is an influential art with major implications for counterterrorism. When providing alternative narratives to terrorist messaging, we rarely address the claims of terrorists directly. Rather, we reframe the arguments to illustrate the grim reality of the utopias preached by the extremists. That steers attitudes — and ultimately behavior — in a direction more beneficial to society.

Hard power still has a role to play with soft power in defeating the forces of violent extremism. But in the end, the fight against terrorism represents a battle of ideas that will be won or lost based on the skills with which we employ our messaging.

As one counterterrorism study put it: “Narratives function on a cognitive plane that is invisible and yet critical to determining what people think, believe, and how they behave. The landscape is complex and is always in a state of competition. It is where a large portion of any battle is waged and fought, often regardless of how much physical power is exerted.”