The Afghan Government Must Improve Public Services to Gain the Loyalty of Citizens

AHMAD FARID FAROZI, FORMER DIRECTOR OF PROGRAMS, DEMOCRACY InTERNATIONAL, AFGHANISTAN

Empirical evidence has shown positive correlations between the quality and efficiency of public service delivery and the level of trust citizens have in their government. For a fragile country such as Afghanistan, where nonstate actors in remote areas compete with the government, the legitimacy of the state essentially depends on the citizens’ trust and confidence.

For rural Afghans, where anti-government elements can exert direct influence, the quality and efficiency of public institutions are what matter most. Therefore, regardless of whether the service provider is a local warlord, an anti-government group or the local government, each realizes it needs to offer better public services to win the hearts and minds of the people.

Evaluating the quality of public services is not rocket science. The moment citizens approach a public institution to resolve a dispute, request protection, pay taxes or renew a passport or driver’s license, they gauge the quality of that experience. Their first contact shapes their perceptions and image of the government. When needs are met legitimately, citizens are satisfied, and trust and confidence in government are restored.

However, if the experience is negative, citizens will seek alternative channels and, given the circumstances of life in rural Afghanistan, possibly turn to nonstate actors. As a result, an inverse relationship is established between citizens’ trust and confidence in state establishments, on the one hand, and anti-state elements on the other.

In fact, this phenomenon has acted as one of the main predictors of security in rural areas of Afghanistan, where citizens have either grown sympathetic to violent extremists or resisted their influence.

The search for solutions

With the generous support of the international community, numerous projects to deliver and improve public services have been executed in Afghanistan. The Afghan government as well as external agencies and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have implemented public service delivery projects in the areas of education; health care; access to justice; issuance of passports, business licenses and land titles; and other basic government services.

These efforts generated temporary positive outcomes but largely failed to deliver the desired sustainable results. There were many reasons for their lack of sustained success — including a focus only on so-called anchor cities. But there were flaws in the overall platform on which the government attempted to improve public service delivery.

While the Afghan public service delivery sector needs transformation from an old-style bureaucratic approach to a modern and citizen-centered approach, the government has been further complicating the old system. Issuance of driver’s licenses, vehicle permits, land titles and passports exemplifies an inefficient, bureaucratic and corrupt process of service delivery that has not improved sufficiently despite repeated efforts.

Consequently, the state public service delivery system remains poor in quality and difficult to access. In addition, the system is inefficient, chaotic, insufficiently citizen-centric, and prone to corruption and bribery.

All too often, the authorities have failed to recognize the importance of a citizen-centric public service delivery system as an effective tool to address some of the most pressing socio-economic issues in Afghan society, particularly those pertaining to rural communities.

Details of the problem

Steps and processes for obtaining some public services are unnecessarily lengthy. A citizen often has to pay bribes to different ranks of government officials to obtain an intended service. If an Afghan wants to resolve a dispute on a small piece of land through the country’s official justice system, the process is often time-consuming and costlier than the land’s value.

Under such circumstance, rural, marginalized and vulnerable citizens remain largely outside the formal Afghan public service delivery system and become the prey of violent extremists. Some people at the rural villages find it easier to get their cases resolved by armed groups operating in the area than by visiting a government office and wasting time and money on the arduous government approval process.

The consequences of this governmental breakdown run even deeper. Many frustrated members of the younger generation either leave the country in search of opportunities elsewhere or join armed groups. Businesses move their capital to more stable and business-friendly markets outside Afghanistan.

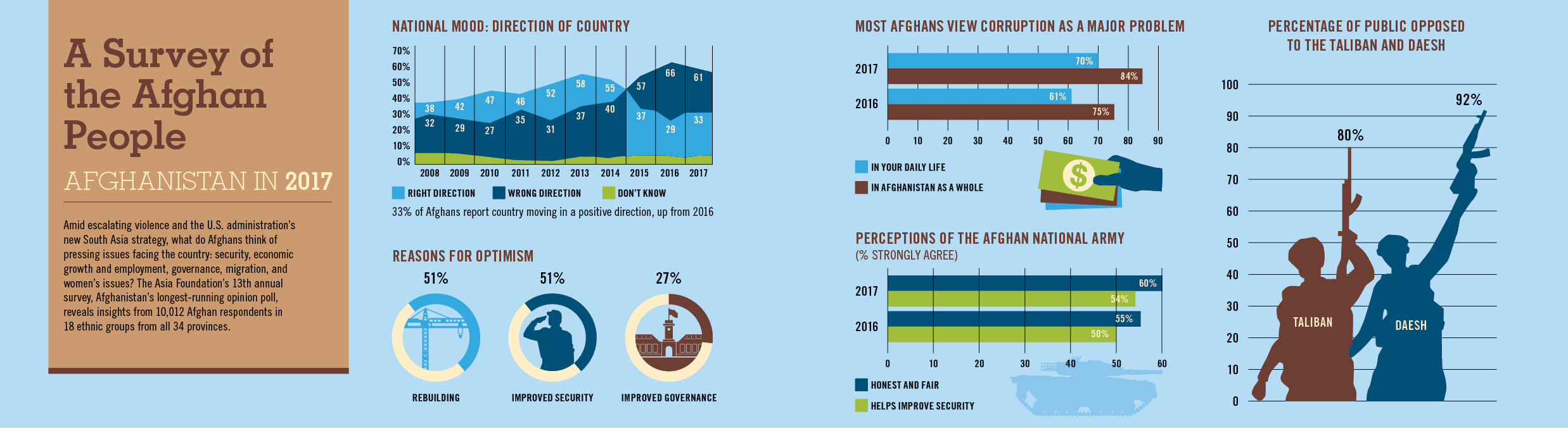

According to a nationwide perception survey conducted by The Asia Foundation in 2017, 61 percent of the Afghan respondents think the country is moving in the wrong direction owing mainly insecurity and fear, lack of economic opportunities and poor governance. The same report indicates that poor governance plays a role in the willingness of 39 percent of Afghans to leave the country, and 84 percent of respondents consider corruption a major issue across Afghanistan.

This survey took pains to get a broad, representative sample of Afghans: The more than 10,000 respondents came from 18 ethnic groups in all 34 provinces.

What needs to be done?

Afghanistan needs to restructure the way it provides services to its citizens. A thorough transformation of the existing outdated system to a citizen-centered system — in which government designs and delivers services based not on the requirements of government but those of citizens — is needed.

This could be achieved by adoption of a comprehensive but pragmatic long-term strategy for delivery of public services, combating corruption and restoring the trust of citizens. It would require streamlining and redefining the work of several overlapping and ineffective organizations. Under a new system, bodies such as the High Office of Oversight and Anti-Corruption, the Anti-Corruption Justice Center, the Administrative Reform Commission, the Supreme Audit Office, and the Asan Khedmat might need to merge and reconfigure themselves.

This fundamental restructuring would enable Afghanistan to combat corruption at all levels: national, subnational, provincial, district and village. It would also create an enabling environment for genuine civil society members to join forces with their government in improving public service delivery in their communities to win the hearts and minds of all citizens across the country.

As a development practitioner who has spent the past 15 years working with local communities, civil society, the government and international donors, I strongly believe that Afghanistan has a golden opportunity and the necessary support to amend the counterproductive approaches of the past and start fresh.

By restructuring public service delivery, Afghanistan and its international supporters will win the hearts and minds of the Afghan people. The alternative is that violent extremist groups will take advantage of government dysfunction to expand their areas of influence in rural areas and increasingly restrict government rule to big cities and the capital.