Population growth in the Middle East and Central and South Asia can be a source of prosperity instead of instability

UNIPATH STAFF | Photos by Reuters

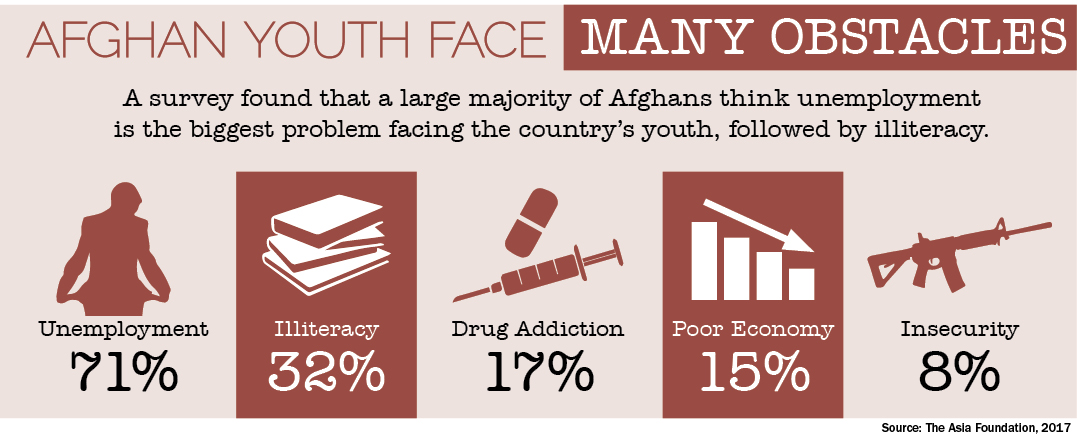

It’s no coincidence that the regions suffering the most violence and political instability over the past 10 years — Syria, Yemen, Afghanistan and Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas — have enormous numbers of young people struggling to stay in school and find jobs.

Demographers from organizations such as the World Bank call it a “youth bulge” — higher birth rates and reduced infant mortality creating a large cohort of citizens under the age of 30.

The World Bank estimates that nearly two-thirds of the populations of countries in the Middle East and North Africa are under 30 years old. And a third of those youths are unemployed and often idle. Some have called the phenomenon a “demographic earthquake.”

Playing off real and imagined societal discontents, extremists have succeeded in enticing some of these young people into radical movements. In the worst cases, young people have enlisted in terrorist organizations such as Daesh and the Taliban, dedicated to inflicting violence on innocents.

Not all the enlistees are committed radicals: Stories are rife about teens and young adults joining armed extremist groups in places such as Yemen and Afghanistan simply for a paycheck that exceeds what they could earn in the regular job market.

“The youth bulge represents a critical challenge to economic development in affected countries, including Egypt, Saudi Arabia, other Gulf countries and Algeria,” writes Sabahat Khan, a Pakistani-born academic at the United Arab Emirates’ Institute for Near East and Gulf Military Analysis.

“The long-term economic prosperity that underpins national security and political stability hinges on providing this growing segment of society with job opportunities as well as education, affordable housing and health care.”

Khan’s comments illuminate an important point: The youth bulge need not be a burden to society. In fact, economic growth and innovation rely on the dynamism of a youthful population willing to take risks for the betterment of their countries.

Yet to harness those benefits, countries of the region can’t simply rely on the prescriptions of the past. This realization is reflected in the initiatives of leaders such as His Royal Highness Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia and His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, vice president and prime minister of the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

Projects in the region include promoting private-sector development, particularly in the field of information technology (IT); reducing reliance on public employment and subsidies; encouraging good government initiatives to build a sense of national unity; and focusing more intensely on primary and secondary education, literacy and vocational training.

And, in cases where food demands are severe because of rapid population growth, countries aim to boost agricultural productivity to provide for hungry mouths.

Exemplifying the efforts of the wealthy Arabian Gulf states to improve the business climate for its people, Sheikh Mohammed in October 2017 launched the One Million Arab Coders initiative. It uses grants from Mohammad bin Rashid Al Maktoum Global Initiatives foundation to provide free online training for Arab young people seeking careers in computer technology.

As the hereditary ruler of Dubai, Sheikh Mohammed has long focused on making his emirate a global economic player. But the IT initiative is unique in that the program is open to young Arabs regardless of nationality. The highest achieving students are eligible for cash prizes.

The most popular private-sector employers in the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Kuwait are technology companies. And a large percentage of youths — up to 39 percent in one survey — seek to create their own businesses within five years. Programs such as Sheikh Mohammed’s aim to give them the skills.

“Many young Arabs have unstoppable potential; all they need is support. We hope this will be the first step in a journey that takes our region towards a brighter future,” Sheikh Mohammed said. “We will not stop launching projects and initiatives to support our Arab communities because the stability of our region relies on it.”

Nurturing the growth of the private sector is a major goal of Crown Prince Mohammed in his efforts to improve the quality of life of young Saudis. Fifty-eight percent of the kingdom’s population is under 30.

The prince promised a more moderate and open Saudi Arabia, less dependent on oil exports and better aligned with the needs of international business. This philosophy is enshrined in the country’s Vision 2030 plan.

Roughly two-thirds of Pakistan’s population consist of poor youths, and about a third of those young people receive little or no formal education or vocational training. But the situation is not hopeless.

In the country’s Federally Administered Tribal Territories (FATA) — long a poorly served part of the country prone to terrorist violence — Pakistan’s central government is trying to radically upgrade the educational system.

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Gov. Iqbal Zafar Jhagra spoke about the bigger picture when he inaugurated a new government high school in February 2018.

“In any society, youth is the real agent of change, and the youth bulge of FATA is approximately 60 percent,” Gov. Jhagra said. “To engage them in healthy activities, efforts are already underway.”

Pakistan’s neighbor Afghanistan has also made large strides in improving education in the past 15 years. In 2018, an estimated 9.2 million children were enrolled in school, a vast improvement over the 1 million enrolled in 2002, according the Afghan Ministry of Education. About 39 percent of those students are girls.

Gov. Jhagra noted that improving education for girls was also important to FATA, where more than 100 schools have been rehabilitated and 408 new teachers trained, allowing 200,000 more children to enroll.

“The FATA secretariat remains committed to addressing the specific needs of the girls’ schools with the aim of improving the basic school infrastructure and ensuring the provision of a safe learning environment,” he said.

Some of the problems with education in Pakistan — such as a dearth of schools teaching knowledge and skills beneficial to a modern economy — also apply to the Middle East. Organizations such as Jordan’s Queen Rania Foundation have made that the focus of their charitable work.

“What the Arab world needs today is an educational revolution; we need a fundamental change that will fulfil every parent’s ambition to provide their child with a quality education,” Her Majesty Queen Rania Al Abdullah of Jordan said.

A 2017 article in the magazine Newsweek told the story of Mohsen Samir Mohammed. A poor factory worker in Cairo, Mohammed worried about having too many children with so little income.

But when his brothers and cousins insulted his manhood, Mohammed, despite living in poverty in Egypt, persuaded his wife to have one child after another. The family lives on stewed fava beans and bread and can’t afford the 15-cent bus ride to send the children to school.

Mohammed’s story illustrates the effects of Egypt’s youth bulge. The pursuit of stable population growth ended decisively with the Muslim Brotherhood government of Mohamed Morsi. Egypt’s current leaders are left to wrestle with the results.

The rising demand for food and water led President Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi to embark on a plan to build thousands of greenhouses on 100,000 acres of mostly arid land throughout northern Egypt. By trapping valuable water, the greenhouses can efficiently produce millions of tons of vegetables for the country’s surging population. Egypt is the world’s largest wheat importer.

Experts suggest Egypt’s youth bulge could spark an economic boom in Egypt — provided the country commits more resources to education. Although the country has successfully enrolled most of its children in schools, international surveys place it near the bottom in quality of primary education.

“A lost generation can easily become a dangerous generation, prone to manipulation by demagogues and extremists who offer simplistic answers and false promises of hope and glory,” said columnist Mark Habeeb of The Arab Weekly.

“While a well-educated generation can boost a society’s overall growth and prosperity, a lost generation becomes a burden, a drag on growth and a constant source of political instability.”