Maj. Gen. (Ret.) Muhammad Samrez Salik, Pakistan Army

sing military force against people within your own borders can be the most dreaded and detested scenario for any army of the world. In Pakistan, misguided and opportunist segments of society took up arms and challenged the writ of the state. Reestablishing order wasn’t possible without kinetic operations that involved collateral damage and property loss. These losses were extremely undesirable but essential for achieving peace.

But after the military cleared and held areas formerly occupied by militants, it was time to win the hearts and minds of the population. Sustaining the authority of the state required providing for the basic needs of the people in these sometimes neglected regions. The Army’s Winning Hearts and Minds (WHAM) campaign has been the mechanism for doing just that.

WHAM projects range from the mundane (installation of hand-operated water pumps and distribution of sports gear) to megaprojects (construction of roads, bridges, dams, hospitals, schools, markets, stadiums, hostels and deradicalization centers. Although Pakistan’s federal and provincial governments financed many of the projects, friendly countries also provided resources. Execution of projects under the auspices of the Army ensured optimum use of available resources. The Army paid special attention to infrastructure damaged during military operations.

Origins of WHAM

To fight the menace of terrorism, the Pakistan Armed Forces, with full backing of the nation, launched operations across the country. Operations Zarb-e-Azb, Raddul Fasaad, Khyber I and II, and intelligence-based operations hunted militants who had disguised themselves in the folds of religion, ethnicity or provincialism. In addition to operations within the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) in Pakistan’s northern regions, operations were conducted against violent militants in Baluchistan, Karachi and other parts of the country. The task was gigantic but so was the resolve of Pakistani forces.

Realizing that defeating terrorism and extremism involves use of both hard and soft power, Pakistan adopted short-term as well as long-term measures. Even during military operations, extrication of innocent people from areas of operations, establishment of temporary camps and repatriation were arduous tasks marvelously executed by the Pakistan Army. As of today, a major portion of displaced people has returned to their respective areas. Back home, they do not find war-ravaged infrastructure and towns, but rather new roads, bridges, hospitals, schools and cadet colleges.

The Pakistan Army has used WHAM operations as a tool of military strategy but also as a means to express deep-rooted love for the Pakistani people. The Pakistan Armed Forces are proud of the nation’s trust, love and support, and stand committed to ensure its safety under all circumstances.

After defeating the insurgents, the military helped local people build houses and sponsored quick-impact projects in affected areas. These projects were undertaken with the help of foreign donors including the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the United Arab Emirates Pakistan Assistance Program (UAEPAP). Multidimensional projects costing $1.1 billion focus on the communications, education, health, power and agricultural sectors.

In 2015, the government of Pakistan announced a rehabilitation strategy in FATA to repair damage, rebuild education and health centers, and reintegrate detainees. The strategy’s five main goals were rehabilitating infrastructure, strengthening law and order, expanding government service delivery, restarting the economy, and strengthening social cohesion and peace building. The projects would take two years. To achieve these objectives, the civil authorities, FATA Secretariat, federal government and Armed Forces increased coordination.

These plans were assigned to military engineers and other professionals and comprised 213 social welfare and developmental projects. For example, UAEPAP financed Cadet College Wana; Sheikh Khalifa Bin Zayed Hospital; Younus Khan Sports Complex in Miran Shah, North Waziristan; and Shahid Afridi Sports Complex Bara in Khyber Agency. Another 257 major and minor projects included the reconstruction of the towns of Miran Shah and Mir Ali and construction of markets at Razmak, Dossali, Damdail, Gharium, Jhalar and Bichhi.

Communications

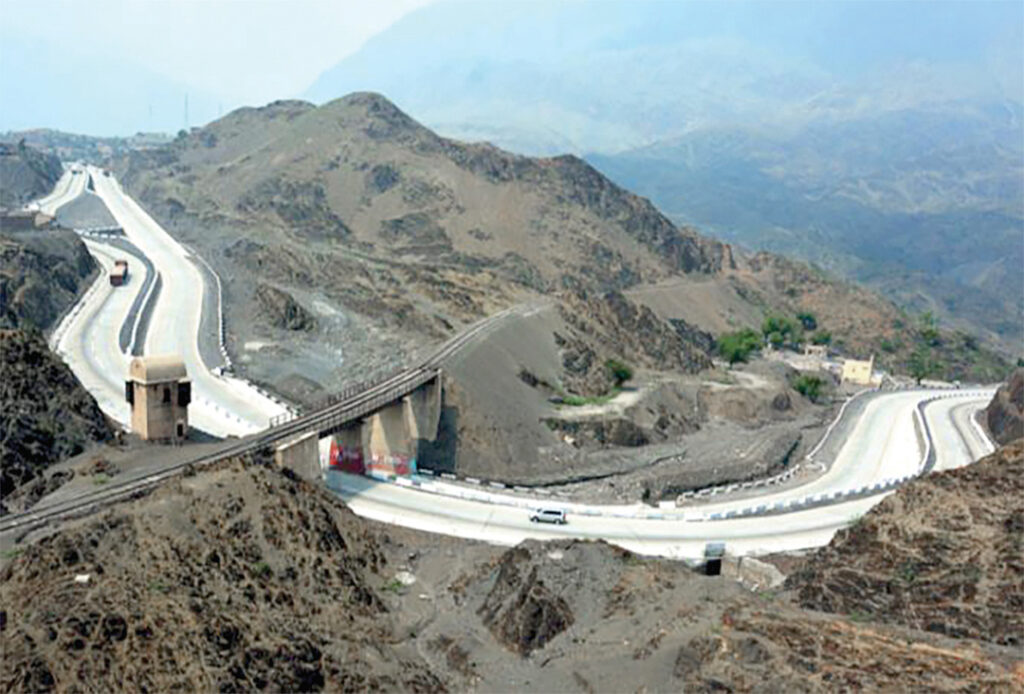

Roads and bridges in FATA have always been inadequate, underdeveloped and badly maintained. Pakistan has been carrying out large-scale infrastructure projects with the help of the United States, the UAE and Saudi Arabia. They are meant to improve accessibility, transport and trade. Rehabilitation of damaged roads and bridges was essential to link isolated communities to other communities. It was well understood that enhanced connectivity will reduce internal rivalries by facilitating interaction amongst the tribesmen. Also, law and order will improve through greater accessibility and logistic support to law enforcement agencies.

So far, projects completed by Pakistan’s Frontier Works Organization (FWO) have included 18 major roads extending 1,205 kilometers, two large bridges and a tunnel. The newly reconstructed Peshawar-Torkham Road is the most significant for accessibility of FATA with landlocked Afghanistan and the Central Asian states. FWO also built the Torkham-Jalalabad Road inside Afghanistan to facilitate two-way traffic between the neighbors.

Afghanistan and Pakistan have a new land link through the Dera Ismail Khan-Wana-Angoor Ada Road, closed more than a century ago. The 80-kilometer Bannu-Miranshah-Ghulam Khan Road is the northern prong of a central trade corridor that passes through prominent towns of North Waziristan and Tochi Pass. The 75-kilometer Wana-Shakai-Makeen Road completed by FWO links Wana, the capital of South Waziristan, with North Waziristan from where the 73-kilometer Makeen-Razmak-Miranshah Road stretches to the Afghan border.

Health

The Taliban targeted government installations to establish a presence in tribal agencies. The health sector faced the brunt as terrorists blew up a large number of clinics and dispensaries. The medical staff abandoned their posts under threat of death.

The unavailability of health care caused feelings of deprivation among the people of FATA and hindered development. The Army, along with the federal and local governments, initiated developmental and rehabilitation projects related to health.

Since 2009, 1,013 health centers, clinics and dispensaries have been established in FATA and the Malakand Division. Nearly 5,400 jobs were created, benefiting 6.4 million people. Bed capacity increased by 680. Newly established permanent and mobile hospitals such as Sheikh Khalifa Bin Zayed and Sheikha Fatima Category A Agency Hospital benefit the people of FATA, Swat and Malakand divisions. Mobile clinics provide hepatitis screening, blood and urine tests, gynecological checkups, and family planning counseling. Moreover, the Army provides special teams of female doctors and nurses to care for women and children. The government deployed 1,050 doctors, 200 female medical officers and 150 nurses to provide rural health care.

The country established training institutes for the medical staff. For example, Paramedical Institute in Swat has become one of the best institutes in Malakand Division for training male and female paramedics. It has an annual capacity of 450 students and benefits about a million people directly and indirectly. A sudden rise in polio cases in Pakistan in 2014 led the Army to organize a national anti-polio campaign. Cases dropped from 306 in 2014 to eight in 2017.

Education

Pakistan has deployed troops in the FATA since 2002 so miscreants could not create sanctuaries in the tribal belt. The most important aspect of the overall fight against militancy is education. Terrorists in the region were vocal critics of education, particularly the education of women, on fanatically religious grounds. Out of 458 educational institutions destroyed (primary schools, secondary schools and colleges), 317 were for boys and 141 were for girls.

Restoration of schools became another challenge for the government and Army. An initial assessment was carried out to determine the damage wrought by the fanatics. In areas where schools were destroyed, Pakistan provided tents and rented space to ensure learning continued during the rebuilding phase.

Outreach campaigns were designed to encourage enrollment and reduce dropout rates, particularly among girls. Student enrollment increased by 300%, and 16,140 staffers were recruited in places such as Cadet College Wana, Girls Degree College Laddha, and the Government College of Technology in Khar.

Youth

Pakistan is blessed with vibrant and talented young people who warrant greater attention to ready them as entrepreneurs and innovators. Training is essential to give them job skills. Through WHAM, the Army engaged young people to promote entrepreneurship and employability. They were also taught to prepare curriculum vitae and polish interview skills.

In 2014, the chief of Army staff announced a youth program for FATA. In addition to career fairs, six-month internships were created. A FATA youth scholarship program engaged 456 students at a cost of 27.4 million rupees, and an Army youth enrollment program attracted 2,637 students.

A lot of students have been admitted to various cadet colleges. Furthermore, 50 students of FATA have been sent abroad to study, and 1,188 FATA youths have been recruited into the Army. Fifty FATA young people joined the Construction Technology Training Institute to learn skills to secure, higher-paying jobs.

Water, power and irrigation

An estimated 40% of cultivated land in FATA and Malakand Division requires irrigation because the area is arid and semiarid. People in Swat relied on distant wells for drinking water. Even worse, floods in 2010 contaminated water and spread disease. To combat this, the UAE has financed 76 water supply projects to provide clean drinking water to the region. The people of Malakand Division and FATA now have systems that use electric pumps powered by generators to dispense clean water to every household. The systems not only provide water but reduce water-borne disease in these areas. More than a million people have benefited in 80 towns and villages. Another 1.3 million residents profited from reconstruction of 736 irrigation systems.

Dhana Irrigation and Water Supply Project, one of the major projects, consists of canals that channel rain and floodwaters to 13,000 acres of farmland near Wana. It also helps conserve and recharge groundwater.

As far as the power sector is concerned, new and refurbished hydroelectric dams and power stations raise regional living standards. For example, completion of Gomal Zam Dam is a big step for the peace and prosperity of South Waziristan. With its huge reservoir of water and completely lined canal network of 260 kilometers, the dam will irrigate 63,086 acres of land in the Tank and D.I. Khan districts. The electricity generated from flowing water can power 2,500 households of South Waziristan.

Gomal Zam Dam was at the epicenter of terrorism. Chinese contractors abandoned construction when militants attacked their camp in 2004. Pakistan’s FWO made great sacrifices to resume the work. Besides the socioeconomic opportunities the dam offers, it aids the environment and tourism. It has effectively controlled flash floods that caused devastation in the past.

Deradicalization

Deradicalization was one of the pillars of WHAM. The basic concept behind the Army’s deradicalization strategy was to remove the psychological burden caused by ideological exploitation and coercion and provide an environment for the restoration of self-respect. It was named “Journey from Darkness to Light.”

One of the first efforts was the Swat Deradicalization Program, which the Army began in 2009 after the Pakistani Taliban were defeated. Most militants apprehended during the operation were teenagers and children trained as suicide bombers. Its four components are psychological rehabilitation, religious counseling, formal education (up to 10th and 12th grades) and vocational training. The ultimate aim was to reintegrate former terrorists and radicals into mainstream civil society.

Programs include Sabaoon for kids between 12 and 18, Rastoon for youths between 19 and 25, and Mishal centers for families of militants. Since 2009, Sabaoon has rehabilitated about 200 militants and Rastoon, 1,196 militants. The Army has converted four large school buildings in Swat into deradicalization centers. Overall, 4,151 people have been deradicalized, and another 599 will rejoin society soon.

Swat’s program became a model for rest of the country. It has been regarded as a complete package for transforming extremists into useful Pakistani citizens.

Displaced people

During Operation Zarb-e-Azb, 337,336 families were displaced from war zones, many of them in North Waziristan. In 2014, the Army established a refugee camp at Bakka Khel near Bannu with two health clinics, a school, four mosques, a jirga hall, two markets and a cricket ground.

The Army promised the displaced that they could return home by the end of 2016. Provision of basic amenities was considered a prerequisite for their repatriation. Rehab work — 500 projects worth 5.35 billion rupees — included construction of schools, mosques and markets. A Citizen Losses Compensation Program handled private claims. Thanks to all these efforts, 95% of North Waziristan’s displaced citizens have returned home.

Social sector

To regain the trust of the people of FATA, the Army stressed reintegration as a part of its WHAM campaign. Troops organized recreational programs in schools and institutions, and the government established a special directorate for sports. A cricket stadium named for Younus Khan opened in Miran Shah. Up till now, 17 new stadiums have been built to benefit the region’s youth.

Furthermore, the Army organized a “Peace Cup” match between a Pakistani military team and a team of British civilians. The match was attended by dignitaries, including Pakistan Army 11th Corps Commander Lt. Gen. Nazeer Butt.

In August 2017, the FATA Secretariat launched a series of “peace games” to celebrate Independence Day. Games included cricket, football, volleyball and wrestling. It sent a message that the tribal belt was no longer a safe haven for terrorists aiming to spread insurgency in Pakistan.

The Pakistan Cycle Federation and the Mohmand Agency local administration, with the support of the Army, organized a Tour de Mohmand to promote peace and health in militancy-stricken areas. More than 70 bikers participated in the 66-kilometer race from Gharsal Pass near the Afghan border to Ghalanai.

To help revive the economy, the Army’s 45th Engineers Division built the Miran Shah Market Complex. The market contains 42 sections with 1,300 shops. It possesses an internal road network, separate parking for trucks and cars, a dedicated electric supply, four bathrooms, a water supply and a lush green park at its center to entertain children.

I am proud to recount these successes of the Army toward the rehabilitation of a troubled region. The Army has contributed to peace in FATA by winning hearts and minds. As much as anything else, the success of the WHAM campaign proves that Pakistan is resilient.