Nonviolent measures to combat violent extremist ideology should supplement military efforts

AHMAD FARID FOROZI, The Asia Foundation

Violence driven by extreme interpretation of religious texts and unjustified aggressive ideologies has taken the lives of hundreds of thousands of men, women and children in Afghanistan since the beginning of conflict in the country in 1978. Millions more have been forced to leave their homes and migrate to other countries. This human catastrophe represents a lost opportunity for development and economic growth, leaving Afghanistan one of the poorest countries of the world.

Today the armed opposition groups (AOGs) — most prominently the Taliban and Daesh — are using a distorted interpretation of religion to legitimize societal destruction and the ongoing brutal attacks on Afghanistan’s government and population. Illustrating this were the terrorist attacks in 2018 on the city of Ghazni that caused death and destruction.

Historically, different regimes in power in the capital Kabul have resorted to force to curb insurgencies and terrorism driven by violent religious ideologues. The current conflict in Afghanistan is no exception. But military force is not sufficient to uproot and repudiate extremist movements eager to take action against the political and social order.

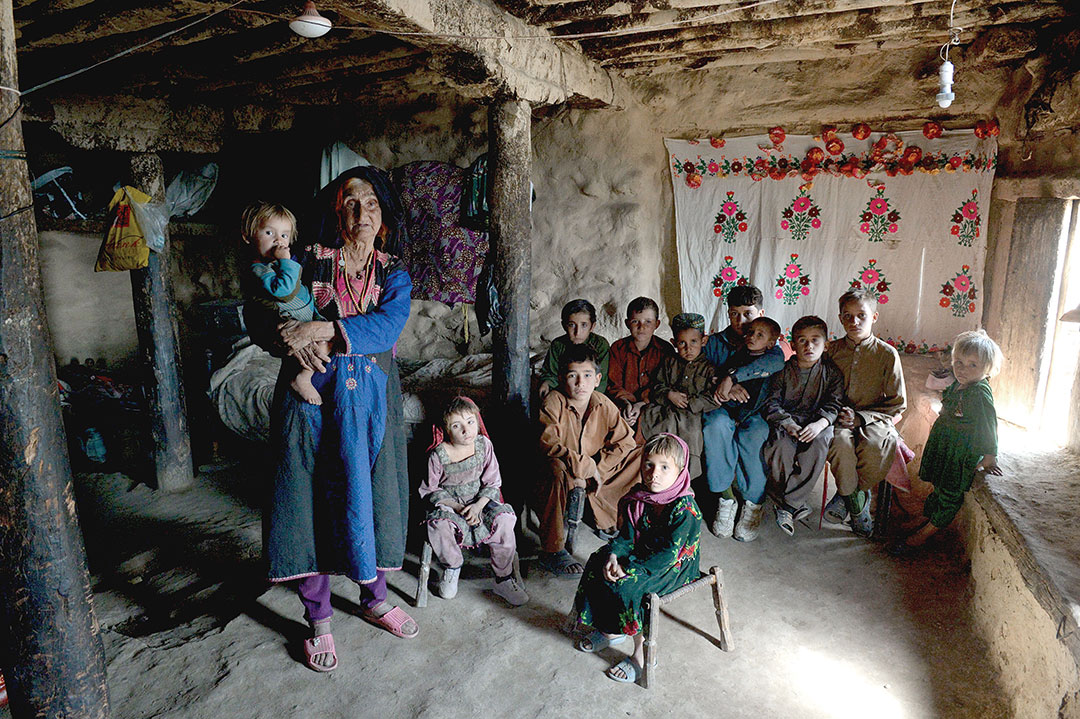

In Afghanistan, we currently have behavioral top-down radicalization wherein radical groups recruit vulnerable young men from impoverished families and prepare them to engage in violence to challenge the political order, social norms and the presence of NATO troops. The ongoing conflict has both its internal as well as cross border and international dynamics.

If the policies of the Afghan government and its foreign allies are effectively focused on addressing internal underlying causes of terrorist recruitment, the external factors shall fail to pose a significant challenge to stability of the country.

The question is what are those internal underlying factors that terrorists exploit to attract and indoctrinate so many young people and wage such a prolonged and exhausting war against coalition forces in Afghanistan? And what nonviolent measures can the Afghan government and its multinational allies undertake to contain the crimes of violent extremists?

Weak public services

In the first place, archaic governance, poor or nonexisting public services, poverty and unemployment have damaged popular confidence in Afghanistan’s central government. In some cases, this lack of confidence helped AOGs stir up opposition to the government and assume control in remote parts of the country.

An in-depth analysis of the current state of public services important to ordinary citizens would provide an overall picture of where gaps exist and what could be done to win people’s confidence. The government and its international partners may need to prioritize investing more in efficient delivery of basic public services to remote rural areas targeted by extremists.

Equally important is the need for extensive reform to improve the country’s business environment. Simplification of business registration processes, streamlining and relaxing the tax system and adopting business protection strategies are fundamental to improving the country’s economic competitiveness.

On the whole, an environment conducive to running private businesses could attract domestic and foreign investment necessary for economic growth and job creation — particularly for youths vulnerable to recruitment by AOGs.

Alienation and disconnectedness

In addition, disconnect between the government and the people left many parents and households in remote rural areas unaware of the vulnerability of their children to insurgents’ propaganda and recruitment campaigns. Government officials typically lacked a systemic mechanism to reach communities and households to make them aware of their responsibilities for protecting their children from exposure to radical indoctrination.

Communities and parents can play an important role in preventing younger children from joining radical groups and AOGs. For parents to play this very much needed role, the government needs to launch awareness campaigns, suitable to the contexts of mostly illiterate and marginalized communities.

The campaigns may involve approaches such as radio announcements, leaflets with infographics, community mobilization events, family counseling, text messaging, religious sermons during Friday prayers and interventions by community elders.

Abuse of social media

The AOGs and the foreign groups and institutions behind them invested significant resources in the use of social networks (Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, blogging websites) to promote their ideologies and recruit individuals for violence. The internet has been particularly effective in attracting the kind of socially ostracized individuals vulnerable to recruitment.

Low cost, wide ranging and available 24/7, social media and the internet are effective tools for radical groups to propagate ideas, mobilize public opinion, and attract new recruits for their twisted and destructive causes.

Technical difficulties and implied free speech limitations make it difficult for the government to trace and disrupt AOGs’ social media campaigns and propaganda. AOGs’ propaganda tools also include night letters (shabnama) and small memory cards holding extremist sermons or videos of training camps.

Systemic and rigorous monitoring of AOGs’ propaganda web and Facebook, YouTube and Twitter pages could inform development of counternarratives to turn people away from radicalization and violence.

Specialized units may be required to perform both monitoring of social media pages belonging to radical groups and timely development and dissemination of counternarratives to diffuse AOG propaganda and prevent youths and children from joining the terrorists.

At the community level, the launch of awareness campaigns could expose the potential risks of specific social media pages exploited by AOGs and their external enablers.

Unregistered madrasas

Equally important is the threat posed by unregistered madrasas which act as incubators for violent extremism and provide a venue for training and recruitment of youths by radical insurgent groups.

With little or no oversight from the government, these religious schools determine their own curriculum, adhere to a severe interpretation of religious texts and promote a narrative of violence. Unregistered madrasas attract impoverished families in rural areas who can ensure their children get free schooling, food and accommodations. What happens next in these madrasas is tragic and dangerous.

Young children are locked in these schools for months and even years without guidance from parents or guardians. They are sometimes sexually abused, and most of these madrasas are controlled by extremists linked to dangerous terrorist groups and intelligence agencies of foreign counties.

Children and youngsters studying in many of these madrasas are systematically brainwashed into becoming suicide bombers or soldiers who follow only two goals — kill or be killed.

Registration and systemic monitoring of all religious madrasas should be considered the core of the government’s counterradicalization and counterinsurgency strategy. Information gathering on the numbers, locations and activities of unregistered madrasas is vital for proper registration and control of madrasa activities.

The government must be prepared to shut down schools unready to register under applicable laws. All registered madrasas data shall be maintained in a dynamic database to assist in systemic monitoring of activities, curriculum and backgrounds and motivations of their instructors.

Moreover, the training and orientation of faculty and staff of registered madrasas should be an integral part of the government strategy to insure that instructors and managers of religious schools are not terrorist sympathizers and teach a tolerant and moderate interpretation of religious texts.

Conclusion

During the past 18 years, the Afghan government and its allies have relied mostly on the use of force as the main pillar of their strategy to contain the ongoing insurgency waged by violent extremist groups. But such a strategy is not enough.

There is still time for a thoughtful shift by the Afghan government and its international friends to realign counter insurgency strategies to address domestic drivers of extremism.

Improving governance, delivering customer-centric public services, fighting corruption, identifying and supporting war-affected families, launching counterradicalization awareness campaigns, strengthening links with communities, rigorously monitoring social media and dissemination of counternarratives, and registering and controlling unregistered madrasas could be part of an overall nonviolent strategy for preventing youths from joining violent groups and containing terrorism.