An analysis of Daesh’s exploitation of social media to spread its malign message

DR. MARLEEN HORMIZ, Isra’ University College

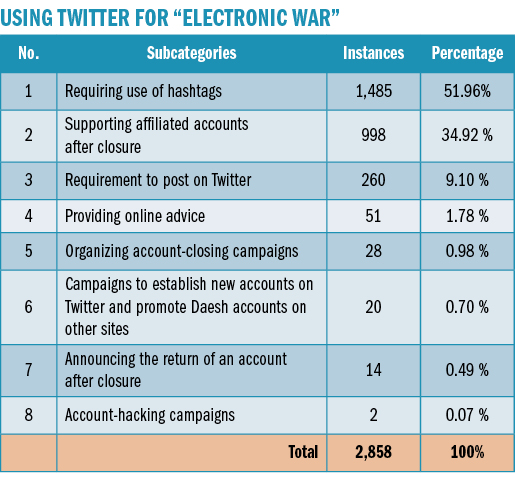

Daesh has transformed Twitter into its electronic province. It orders its followers and supporters to post on the site to bolster the organization, recruit new members and collect donations. The organization set up a “bank of accounts” on Twitter to hand out new accounts to supporters whose accounts are shut down to ensure that they can quickly get back to posting on Twitter. It ordered its supporters to use hashtags in their tweets, which they did intensively, and the organization’s psychological warfare on Twitter became a “hashtag war.”

Daesh also set up a “hacking division,” a group of hackers that breaches important global websites. To give just a couple of examples, the division posted documents containing dozens of names, addresses and phone numbers that it claimed were for Saudi intelligence officers. It also threatened to hack into White House sites and other accounts in the United States.

These terrorists established something called the Granddaughters of Aisha Foundation, women who make multimedia posts featuring news written and published on the websites of the Daesh and the Amaq News Agency. These posts are linked by audio to Al-Bayan Radio’s posts, digital photos and video clips of suicide or sleeper operations, or clips of newly released videos.

The Granddaughters of Aisha have played a major role in luring new recruits and posting instructions for people who decide to immigrate to territory occupied by the organization, complete with information about what they need to do at each step of the trip. It also provides electronic advice on how to protect accounts from hacking. On top of this are techniques for making explosives, plus running accounts with the mission of identifying various types of weapons and combat methods and converting certain civilian vehicles for military use.

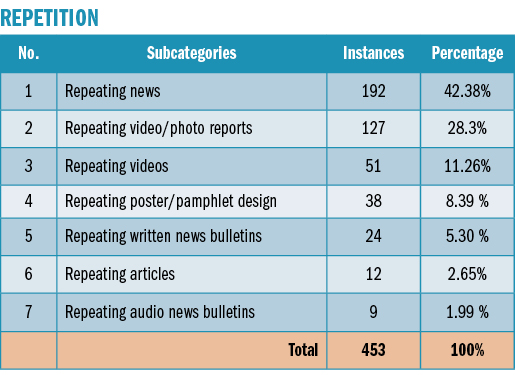

Daesh has also focused on a strategy of repetition in posting tweets to ensure that tweets are not deleted. This involves the following:

- Repeated posting of the same content several times over short or long periods.

- Repeated posting of the same content among groups of Daesh accounts.

- Repetition of the same content in several forms in a single tweet (text, photo, video).

- Repeated posting of the same video and audio files at more than one link.

- Using special technology or systems that post online automatically, such as posting 13 tweets at once every 30 seconds.

Through examination of eight active pro-Daesh accounts (Kawaser Al-Nashr, Ajnad Al-Osrah, Kasshaf, Al-Noemi ibn Al-Ramadi, Abu Othman Al-Qannas, Abu Ibada Al-Ansari, Hawwaa Brayef, Abu Isdar), 2,380 tweets were analyzed between February 10, 2016, and May 10, 2016. The tweets included an array of journalism, as shown in the table below:

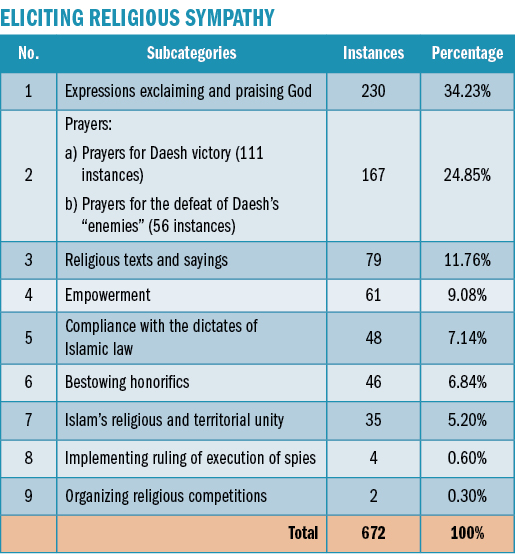

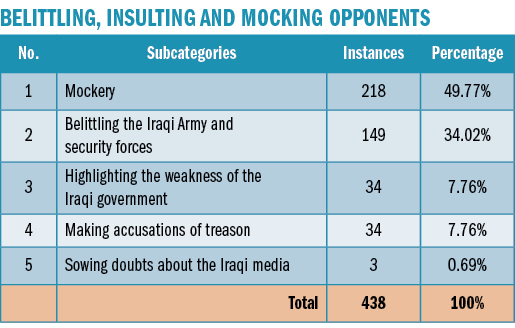

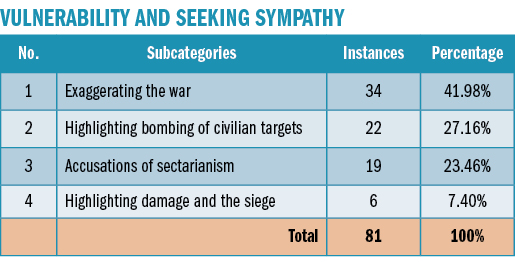

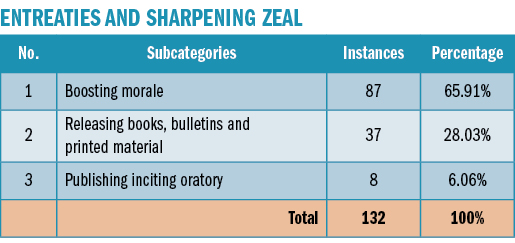

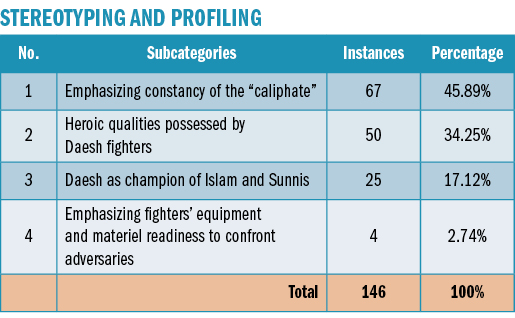

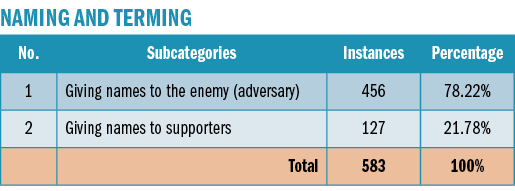

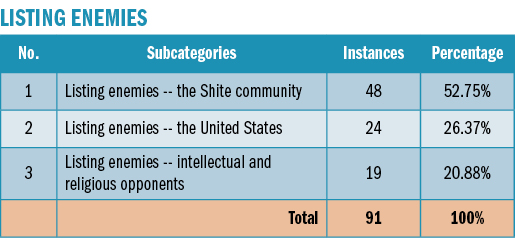

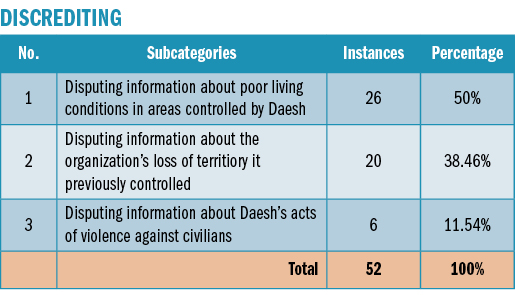

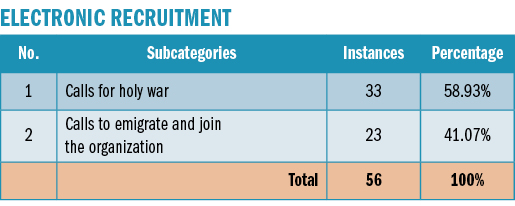

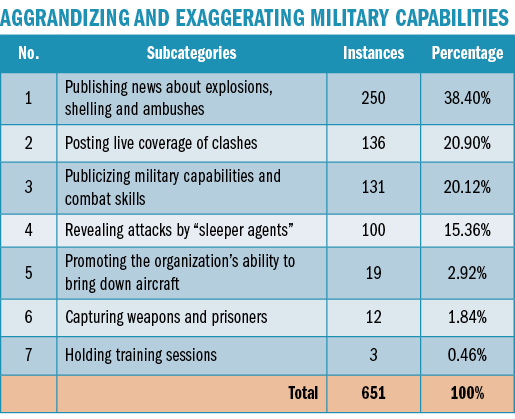

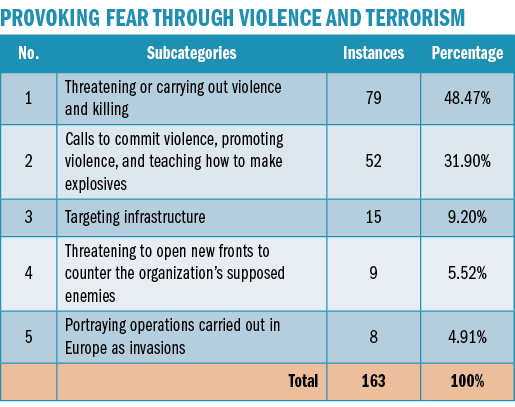

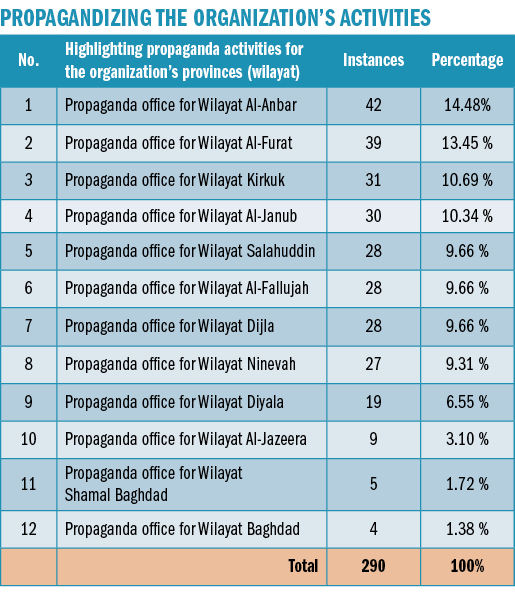

The following tables show the psychological warfare methods apparent in the content analysis of tweets posted by the eight accounts named above during a three-month period:

Conclusions

Daesh used 13 propaganda and psychological warfare methods in its written content, including two new methods: electronic recruitment and promoting the organization’s civil activities. This confirms that the organization’s supporters include people proficient in psychological warfare. In addition, Daesh used electronic warfare to psychological effect with tools that became available with the emergence of the post-interactivity contact that characterizes Twitter.

Daesh’s psychological warfare on Twitter can be described as a “hashtag war” because it uses hashtags as one of the primary weapons, penetrating the most widely circulated hashtags regardless of topic. The terrorists’ psychological warfare on Twitter is notable for the use of multimedia content (text + sound + digital photos + video + infographics).

It worked to put together campaigns to support pro-Daesh accounts after their closure. It did this by providing new, ready-made accounts and promoting affiliated accounts following deletion, on top of organizing campaigns to report anti-Daesh accounts. The organization’s propaganda wings also intensified the pursuit of electronic psychological warfare when subjected to military attacks on the ground. The organization focused on eliciting the audience’s religious sympathy and affecting them emotionally, seeking to win them over by exploiting religious feeling.

Based on the above conclusions, Daesh will remain active online after its loss of territory in Iraq and will use electronic and social media warfare to continue gaining supporters and to target important local and international institutions and infrastructure.

Recommendations

To prevent terrorists from exploiting the nature of social media to spread extremist ideas and attract young people, Iraqi governmental and private academic and research institutions should hold annual conferences and regular seminars on electronic psychological warfare practiced by terrorist organizations. This would educate Iraqi society about the danger of this strategy and identify ways to combat it by publicizing conclusions and recommendations for educational, social and psychological institutions.

Furthermore, Iraqi security agencies concerned with psychological warfare should use academic studies and research to help organize psychological warfare resistance or offense campaigns. Work should be done to conduct psychological and sociological studies on the psychological and sociological impacts on Iraqis’ personalities in the areas that the organization controlled for three years, especially on children and adolescents, to provide instruction on ways to eliminate vestiges of the terrorist organization’s ideas from their minds.

Awareness campaigns should be aimed at children’s guardians to inform them of the danger of their children following content posted by Daesh on social media sites, especially Twitter. Considering that the organization will likely remain active online in broader, higher quality, and more intensive ways after its loss of territory, Iraqi security institutions specializing in psychological warfare should coordinate with similar Arab and international institutions so that they can learn from Iraq’s experience with Daesh’s psychological warfare, especially given that it blended traditional and electronic practices, and to spread those lessons internationally. The relevant state institutions should outline a proactive psychological warfare strategy and provide the tools and resources required to implement this strategy when the need arises.